Showing posts with label George Washington. Show all posts

Showing posts with label George Washington. Show all posts

Monday, July 1, 2019

John and Abigail Adams Gooseberry Fool

As a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, John Adams was one of the fiercest advocates of the Declaration of Independence. Contrary to popular belief, the declaration wasn't signed by all of the delegates on July 4, 1776. Instead, it was initially approved on July 2, 1776. The delegates then continued debating and slightly revised it the following day and formally adopted it on the Fourth of July. Most historians agree that the Declaration wasn’t signed by all the delegates (with a few holdouts) until nearly a month later, on August 2, 1776.

Nevertheless, on July 3, 1776, John Adams wrote a letter to his wife Abigail, describing these momentous events. This, in part, is what he wrote:

The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival...It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.

Although no one knows what the delegates ate on those momentous days, biographers say that Adams was fond of Green Sea Turtle Soup, Indian Pudding and other simple foods of his New England youth. Gooseberry Fool, a traditional eighteenth century British and early American dish, was another Adams family favorite.

As an example of how national foodways change over time, gooseberries were abundant in John's day, but aren't widely available in the United States today. So, if you can't find gooseberries in your local grocery store, you can use blueberries or raspberries. Either way, this delicious, nutritious, and refreshingly sweet little treat would make a great addition to your Fourth of July festivities this week!

If you'd like to whip up some Gooseberry Fool today, here's a simple and simply delicious recipe to try from epicurious.com

3 cups pink or green gooseberries (or blueberries)

1/2 cup granulated sugar

1/2 cup well-chilled heavy cream

1/4 cup crème fraîche

1/4 cup superfine granulated sugar

Pull off tops and tails of gooseberries and halve berries lengthwise. In a heavy skillet cook berries and granulated sugar over moderate heat, stirring occasionally until liquid is thickened, about 5 minutes. Simmer mixture, mashing with a fork to a coarse puree, 2 minutes more. Chill puree, covered, until cold, about 1 hour, and up to 1 day.

In a bowl with an electric mixer beat heavy cream with crème fraîche until it holds soft peaks. Add superfine sugar and beat until mixture just holds stiff peaks. Fold chilled puree into cream mixture until combined well. Fool may be made 3 hours ahead and chilled, covered.

Credit: Declaration of Independence, painting by John Trumball

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

George Washington's Thursday Dinners

When George Washington was inaugurated in March, 1789, some of the most pressing questions facing the new nation involved social manners and etiquette. This may seem trivial today, but back then, George and his fellow patriots had just fought a long war against the British Crown and they wanted to be sure that the American people would never mistake their president for a king.

How much pageantry should surround the office of the presidency? How elaborate should presidential dinners be? And how should the new president be addressed? As “His Excellency” or “His Mightiness”? These were questions of great importance when George Washington took the Oath of Office on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City on April 30, 1789.

Immediately after taking office, Washington distributed questionnaires to his advisors, soliciting their opinions regarding the basis of “a tenable system of etiquette.” After much discussion, it was decided that George would be addressed as President Washington or simply Mr. President.

It was also decided that “levees” (receptions) would be held each Tuesday afternoon for "foreign ambassadors and other strangers of distinction” and that congressional dinners would be held each Thursday. Friday nights were chosen for Martha Washington’s “Drawing Rooms” and the remaining days were reserved for state banquets and personal entertaining.

Despite his desire to avoid the trappings of monarchy, George's Thursday dinners were truly fit for a king. "Dinners would begin promptly at four o’clock," according to culinary historian Poppy Cannon, and would often consist of three "bountiful" courses, the first two of which typically consisted of fifteen or twenty different dishes – all brought to the table at once!

A menu from Martha Washington’s family cookbook reveals just how elaborate these dinners could be. For a first course, she suggested serving Boiled Turkey, Baked Salmon, Shoulder of Mutton, Chicken Patties, Baked Ham, Stewed Cabbage, Scotch Collops, Pork Cutlets and Sauce Robert with Mashed Potatoes, Maids of Honors, Dressed Greens, French Beans, Oyster Loaves and Celery Sauce.

This course would be followed by Asparagus a la Petit Poi, Crayfish in Sauce, Fruit in Jelly, Lamb Tails, Partridges, Poached Salmon, Wild Duck, Roasted Hare, Sweetbreads, Plovers, Prawns, and Chardoons with Fricassed Birds, Rhenish Cream and custard.

After this course, the table cloth was removed and fresh glasses and decanters of wine were placed on the table with all kinds of fruits and nuts. If Martha and other ladies were present, they would excuse themselves at this point and the men would settle down (with very full bellies!) to talk about politics and other important affairs of the day.

Although Martha's dishes might be difficult to duplicate today, you can try this fabulous recipe for Poached Salmon with Creamy Dill Sauce or this one for Poached Salmon with Dill from simplyrecipes.com.

1 to 1½ pounds salmon fillets

½ cup dry white wine (a good Sauvignon Blanc)

½ cup water

A few thin slices of yellow onion and/or 1 shallot, peeled and sliced thin

Several sprigs of fresh dill or sprinkle of dried dill

A sprig of fresh parsley

Put wine, water, dill, parsley and onions in a saute pan, and bring to a simmer on medium heat. Place salmon, skin-side down on the pan. Cover and cook for 5 minutes. Season with freshly ground black pepper and enjoy.

FOOD FACT: If you visit Mount Vernon someday, be sure to stop by the Mount Vernon Inn Restaurant which serves such authentic colonial appetizers as Peanut and Chestnut Soup, Colonial Hoe Cakes, and Fried Brie with Strawberry Sauce. Dinner menu items include Filet Mignon wrapped in Virginia Pepper Bacon; Roast Duckling with “George Washington’s favorite Apricot Sauce,” and Stuffed Pork Loin with Opium Sauce!

Tuesday, September 27, 2016

The Battle of the Chesapeake and the Signifance of Food in Military History

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes, was a critical naval battle in the Revolutionary War. It also provides a fabulous example of how world and military history has been partly shaped by food.

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes, was a critical naval battle in the Revolutionary War. It also provides a fabulous example of how world and military history has been partly shaped by food. The battle took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake on September 5, 1781 between “a British fleet led by Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves and a French fleet led by Rear Admiral François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse.” Although it didn't immediately end the war, the victory by the French was a major strategic defeat for the British because it prevented the Royal Navy from resupplying food, troops, and other provisions to General Charles Cornwallis’ blockaded forces at Yorktown.

Equally important, it prevented interference with the delivery of troops and provisions that were en route to General George Washington's army through the Chesapeake. Six weeks later, with the British forces tired, hungry, trapped, and depleted, General Cornwallis surrendered his army to General Washington after the Seige at Yorktown, which effectively ended the war and forced Great Britain to later recognize the independence of the United States of America.

Of course, many other critical political, economic, and military forces contributed to the end of the Revolutionary War, but that doesn't in any way diminish the fact that food (or the lack of it) has played an important role in the course of world and military history.

FAST FACT: During the Civil War, General Winfield Scott observed that, "The movements of an army are necessarily subordinate...to considerations of the belly." And the famous French emperor Napoleon valued pickles as a food source for his armies so much that he offered the equivalent of $250,000 to the first person who discovered a way to safely preserve food. The man who won the prize in 1809 was a confectioner named Nicolas Appert, who discovered that food wouldn’t spoil if you removed the air from a bottle and boiled it long enough. This process, of course, is known as canning and Appert's discovery remains one of the most pivotal events in the modern history of food and human nutrition.

Image: Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown by John Trumbull (1787)

Sunday, December 13, 2015

Benjamin Harrison and the First Decorated Christmas Tree at the White House

Benjamin Harrison’s presidency began with a dramatic, three-day centennial commemoration of George Washington’s inauguration as the first president of the United States. The festivities began on April 28, 1889 with a reception in the White House, followed by a reenactment of George Washington’s crossing of New York Harbor by barge under a fuselage of gun salutes and fireworks. The evening was capped with a lavish banquet, featuring thirteen wines and thirteen toasts in honor of the original thirteen colonies.

Benjamin Harrison’s presidency began with a dramatic, three-day centennial commemoration of George Washington’s inauguration as the first president of the United States. The festivities began on April 28, 1889 with a reception in the White House, followed by a reenactment of George Washington’s crossing of New York Harbor by barge under a fuselage of gun salutes and fireworks. The evening was capped with a lavish banquet, featuring thirteen wines and thirteen toasts in honor of the original thirteen colonies. Despite the initial fanfare, Harrison and his family dined rather modestly during their four years in the White House, and it has been said that their Christmas dinner was about as unpretentious as the family itself. According to culinary historian Poppy Cannon:

The dinner began with Blue Point oysters on the half shell, followed by consomme a la Royale, chicken in patty shells, and then the piece de resistance, stuffed roast turkey, cranberry jelly, Duchess potatoes and braised celery. Then came terrapin a la Maryland, lettuce salad with French drssing, and assorted desserts: minced pie, American plum pudding, tutti fruitti ice cream. For those still hungry, ladyfingers, Carlsbad wafers, and macaroons were passed, followed by fruit and coffee...

But of all White House holiday traditions, the Harrison's are perhaps most well-known for setting up the first decorated Christmas tree in the White House. According to White House historians, it was on the morning of December 25, 1889 that President Harrison "gathered his family around the first indoor White House Christmas tree. It stood in the upstairs oval room, branches adorned with lit candles. First Lady Caroline Harrison, an artist, helped decorate the tree."

As our nation's First Lady, Mrs. Harrison set the stage for what would eventually become a White House holiday tradition. But not all First Families after the Harrisons set up Christmas trees in the White House. First Lady Grace Coolidge did in the 1920s; however, it was First Lady "Lou" Henry Hoover who started the custom in 1929 when she oversaw the decoration of the first "official" tree. Since then, the honor of trimming the main White House Christmas tree has belonged to the First Ladies. According to the White House Historical Association:

In 1961, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy began the tradition of selecting a theme for the official White House Christmas tree. She decorated a tree placed in the oval Blue Room with ornamental toys, birds and angels modeled after Petr Tchaikovsky's "Nutcracker Suite" ballet. Mrs. Kennedy reused these ornaments in 1962 for her children's theme tree. Set up in the North Entrance, this festive tree also featured brightly wrapped packages, candy canes, gingerbread cookies and straw ornaments made by disabled or senior citizen craftspeople throughout the United States.

The Lyndon B. Johnson Administration began during a time of great uncertainty. In November 1963, the assassination of President Kennedy had stunned America. New First Lady Claudia "Lady Bird" Johnson certainly felt a desire to help the nation heal. She chose comforting and nostalgic holiday decor during her White House years. Her 1965 and 1966 Blue Room Christmas trees were decorated in an early American theme. They featured thousands of small traditional ornaments, including nuts, fruit, popcorn, dried seedpods, gingerbread cookies and wood roses from Hawaii...

Handmade crafts set the theme for First Lady Betty Ford's 1974 Blue Room tree. Emphasizing thrift and recycling, Mrs. Ford used ornaments made by Appalachian women and senior citizen groups. Swags lined with patchwork encircled the tree. She kept this quaint feel in 1975 for her "old-fashioned children's Christmas" theme. Experts from Colonial Williamsburg adapted paper snowflakes, acorns, dried fruits, pinecones, vegetables, straw, cookies and yarn into ornaments...

In 2010, the theme for the Obamas first holiday season at the White House was "Shine, Give, Share," which offered a paid tribute to our troops, veterans and their families throughout the White House. The tour featured 37 Christmas trees and a huge gingerbread model of the White House made of 400 pounds of gingerbread, white chocolate, and marzipan. The centerpiece was the official Christmas tree that honored our men and women in uniform and featured beautiful and moving holiday cards created by military children.

The holiday décor also included "a bounty of Bos!" With a playful nod to the First Dog, the tour featured five Bo topiaries made from materials like felt, buttons, pom poms and candy, including marshmallows and 1,911 pieces of licorice!

FAST FACT: Christmas was not an official federal holiday until an Act of Congress signed into law by Ulysses S. Grant in June of 1870. Prior to then, a few state governments celebrated the day. The bill also declared that New Year’s Day and the 4th of July would be national holidays.

Tuesday, December 1, 2015

George Washington's Ice House at Mount Vernon

So did you know that one of George Washington’s favorite desserts was ice cream? In fact, he liked this soft, creamy treat so much that he had an ice house constructed near his Mount Vernon home so that he and his family could eat ice cream often.

So did you know that one of George Washington’s favorite desserts was ice cream? In fact, he liked this soft, creamy treat so much that he had an ice house constructed near his Mount Vernon home so that he and his family could eat ice cream often. Historians say that Washington’s icehouse was located on a riverbank about 75 yards from the Potomac. To store ice, Washington’s slaves had to use chisels and axes to pull large chunks of ice from the frozen river during the wintertime and then haul them to the icehouse where they were stacked in layers and stored for use throughout the spring and summer.

Before constructing his ice house, Washington sought advice from his friend and fellow patriot Robert Morris, who had an ice house at his home at 6th & Market Streets in Philadelphia. In a letter to Washington, Morris provided a detailed account of how his ice house had been constructed:

My Ice House is about 18 feet deep and 16 square, the bottom is a Coarse Gravell & the water which drains from the ice soaks into it as fast as the Ice melts, this prevents the necessity of a Drain...the Walls of my Ice House are built of stone without Mortar...On these [walls] the Roof is fixed...I nailed a Ceiling of Boards under the Roof flat from Wall to Wall, and filled the Space between the Ceiling and the Shingling of the Roof with Straw so that the heat of the Sun Cannot possibly have any Effect...

The Door for entering this Ice house faces the north, a Trap Door is made in the middle of the Floor through which the Ice is put in and taken out. I find it best to fill with Ice which as it is put in should be broke into small pieces and pounded down with heavy Clubs or Battons such as Pavers use, if well beat it will after a while consolidate into one solid mass and require to be cut out with a Chizell or Axe. I tried Snow one year and lost it in June. The Ice keeps until October or November and I believe if the Hole was larger so as to hold more it would keep untill Christmas...

Although Morris didn't mention what he stored in his icehouse, we do know that the Washingtons used theirs to preserve meat and butter, chill wine, and make ice cream and other frozen delicacies for their many guests at Mount Vernon.

Of course, George Washington wasn’t the only president who enjoyed ice cream. Accounts of it often appear in letters describing the many elegant dinner parties hosted by James and Dolley Madison, and the dish frequently appears in visitors' accounts of meals with Thomas Jefferson.

One particular guest wrote: "Among other things, ice-creams were produced in the form of balls of the frozen material inclosed in covers of warm pastry, exhibiting a curious contrast, as if the ice had just been taken from the oven." If you'd like to whip up some ice cream contained in warm pastry for your next dinner party, here is a simple and delicious recipe to try from puffpastry.com

1/2 of a 17.3-ounce package pastry sheets, 1 sheet, thawed

1 pint chocolate ice cream, softened

1 pint strawberry ice cream, soft

Chocolate fudge topping

Heat the oven to 400°F. Unfold the pastry sheet on a lightly floured surface. Cut the pastry sheet into 3 strips along the fold marks. Place the pastries onto a baking sheet. Bake for 15 minutes or until the pastries are golden brown. Remove the pastries from the baking sheet and let cool on a wire rack for 10 minutes. Split each pastry into 2 layers, making 6 in all.

Reserve 2 top pastry layers. Spread the chocolate ice cream on 2 bottom pastry layers. Freeze for 30 minutes. Top with another pastry layer and spread with the strawberry ice cream. Top with the reserved top pastry layers. Freeze for 30 minutes or until the ice cream is firm. Drizzle with the chocolate topping.

FAST FACT: In 1790, Robert Morris's house at 6th & Market Streets became the Executive Mansion of the United States while Philadelphia served as the temporary capital of the nation. Morris' icehouse was used by President Washington and his household until 1797, and by President John Adams and his family from 1797 to 1800.

For my new literary agent profile and submission guidelines, click here

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

George Washington, the Battle of the Chesapeake, and the Significance of Food in Military History

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes, was a critical naval battle in the Revolutionary War. It also provides a fabulous example of how world and military history have been shaped in part by food.

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes, was a critical naval battle in the Revolutionary War. It also provides a fabulous example of how world and military history have been shaped in part by food. The battle took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake on September 5, 1781 between a British fleet led by Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves and a French fleet led by Rear Admiral François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse. Although it didn't end the war, the victory by the French was a major strategic defeat for the British because it prevented the Royal Navy from resupplying food, troops, and other provisions to General Charles Cornwallis’ blockaded forces at Yorktown.

Equally important, it prevented interference with the delivery of provisions that were en route to General George Washington's army through the Chesapeake. Six weeks later, with the British forces trapped, hungry and depleted, Cornwallis surrendered his army to George Washington after the Seige at Yorktown, which effectively ended the war and forced Great Britain to later recognize the independence of the United States.

Of course, many other critical factors contributed to the end of the war, but that doesn't diminish the fact that food (or the lack of it) has played an enormously important role in the course of world and military history.

FAST FACT: General Winfield Scott observed that, "The movements of an army are necessarily subordinate...to considerations of the belly." And Napoleon valued pickles as a food source for his armies so much that he offered the equivalent of $250,000 to the first person who discovered a way to safely preserve food. The man who won the prize in 1809 was a French chef and confectioner named Nicolas Appert who discovered that food wouldn’t spoil if you removed the air from a bottle and boiled it long enough. This process, of course, is known as canning and Appert's discovery was one of the most pivotal events in the modern history of food and human nutrition!

Monday, February 9, 2015

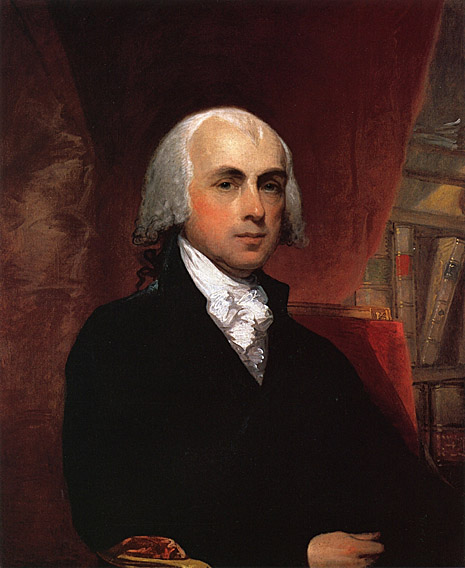

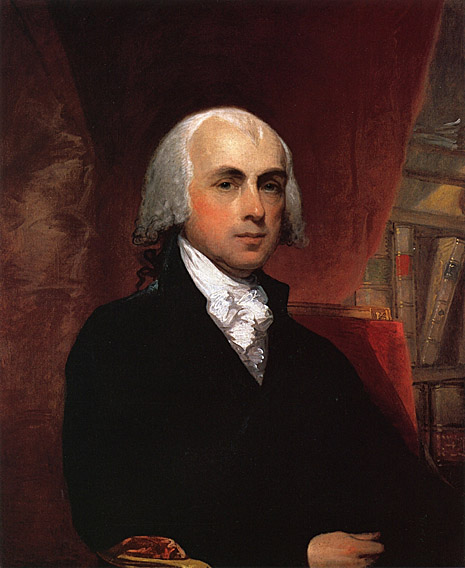

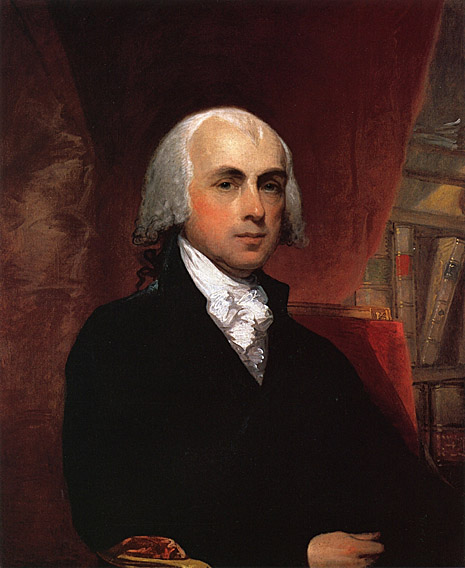

James Madison, the Potomac Oyster Wars, and the Path to the Constitutional Convention

So

you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the

Bill of Rights. But what you might not know is that he also played a major role

in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars, which helped pave

the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly

goes:

So

you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the

Bill of Rights. But what you might not know is that he also played a major role

in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars, which helped pave

the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly

goes:In the seventeenth century, watermen in Maryland and Virginia battled over ownership rights to the Potomac River. Maryland traced its rights to a 1632 charter from King Charles I which included the river. At the same time, Virginia laid its claims to the river to an earlier charter from King James I and a 1688 patent from King James II, both of which also included the river.

In 1776, after more than a century of conflict, Virginia ceded ownership of the river but reserved the right to “the free navigation and use of the rivers Potowmack and Pocomoke." Maryland rejected this reservation and quickly passed a resolution asserting total control over the Potomac. After the Revolution, battles over the river intensified between watermen from both states.

To resolve this problem, leaders from Maryland and Virginia appointed two groups of commissioners which, at the invitation of George Washington, met at Mount Vernon in May of 1785. James Madison led the Virginia contingent and Samuel Chase led the Maryland delegation. Their discussions led to the Compact of 1785, which allowed oystermen from both states free use the river.

Peace prevailed until the supply of oysters began to dwindle, at which point Maryland re-imposed harvesting restrictions. Virginia retaliated by closing the mouth of the Chesapeake and watermen from both states engaged in bloody gun battles which lasted, with periodic breaks, for more than a century.

Today, these battles are known as the Potomac Oyster Wars. They're important in their own right but they have a larger historical significance because they revealed one of the main weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which was that the federal government didn't have the power to control commerce among the states, a setup that was creating constant chaos and conflict.

With this problem in mind, Madison and the others who convened at Mt. Vernon in May of 1785 agreed to meet the following year at Annapolis to discuss the need for a stronger federal government. Not many delegates showed up and so they agreed to convene the following May in Philadelphia, which is, of course, where the Constitution was drafted.

And so NOW you know how James Madison and a little bivalve from the Potomac helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention!

FAST FACT: Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government didn't have the power to raise an army, regulate interstate commerce, or coin money for the country. To pass a law, Congress needed the approval of nine out of the 13 states, and in order to amend the Articles it needed the approval of all 13 states, which made it nearly impossible to get anything done! The Articles also didn't provide for an Executive or Federal branch so there was no separation of powers.

Monday, December 8, 2014

George Washington's Ice House at Mount Vernon

So did you know that one of George Washington’s favorite desserts was ice cream? In fact, he liked this soft, creamy treat so much that he had an ice house constructed near his Mount Vernon home so that he and his family could eat ice cream often.

So did you know that one of George Washington’s favorite desserts was ice cream? In fact, he liked this soft, creamy treat so much that he had an ice house constructed near his Mount Vernon home so that he and his family could eat ice cream often. Historians say that Washington’s icehouse was located on a riverbank about 75 yards from the Potomac. To store ice, Washington’s slaves had to use chisels and axes to pull large chunks of ice from the frozen river during the wintertime and then haul them to the icehouse where they were stacked in layers and stored for use throughout the spring and summer.

Before constructing his ice house, Washington sought advice from his friend and fellow patriot Robert Morris, who had an ice house at his home at 6th & Market Streets in Philadelphia. In a letter to Washington, Morris provided a detailed account of how his ice house had been constructed:

My Ice House is about 18 feet deep and 16 square, the bottom is a Coarse Gravell & the water which drains from the ice soaks into it as fast as the Ice melts, this prevents the necessity of a Drain...the Walls of my Ice House are built of stone without Mortar...On these [walls] the Roof is fixed...I nailed a Ceiling of Boards under the Roof flat from Wall to Wall, and filled the Space between the Ceiling and the Shingling of the Roof with Straw so that the heat of the Sun Cannot possibly have any Effect...

The Door for entering this Ice house faces the north, a Trap Door is made in the middle of the Floor through which the Ice is put in and taken out. I find it best to fill with Ice which as it is put in should be broke into small pieces and pounded down with heavy Clubs or Battons such as Pavers use, if well beat it will after a while consolidate into one solid mass and require to be cut out with a Chizell or Axe. I tried Snow one year and lost it in June. The Ice keeps until October or November and I believe if the Hole was larger so as to hold more it would keep untill Christmas...

Although Morris didn't mention what he stored in his icehouse, we do know that the Washingtons used theirs to preserve meat and butter, chill wine, and make ice cream and other frozen delicacies for their many guests at Mount Vernon.

Of course, George Washington wasn’t the only president who enjoyed ice cream. Accounts of it often appear in letters describing the many elegant dinner parties hosted by James and Dolley Madison, and the dish frequently appears in visitors' accounts of meals with Thomas Jefferson.

One particular guest wrote: "Among other things, ice-creams were produced in the form of balls of the frozen material inclosed in covers of warm pastry, exhibiting a curious contrast, as if the ice had just been taken from the oven." If you'd like to whip up some ice cream contained in warm pastry for your next dinner party, here's a simple recipe to try from puffpastry.com

1/2 of a 17.3-ounce package pastry sheets, 1 sheet, thawed

1 pint chocolate ice cream, softened

1 pint strawberry ice cream, soft

Chocolate fudge topping

Heat the oven to 400°F. Unfold the pastry sheet on a lightly floured surface. Cut the pastry sheet into 3 strips along the fold marks. Place the pastries onto a baking sheet. Bake for 15 minutes or until the pastries are golden brown. Remove the pastries from the baking sheet and let cool on a wire rack for 10 minutes. Split each pastry into 2 layers, making 6 in all.

Reserve 2 top pastry layers. Spread the chocolate ice cream on 2 bottom pastry layers. Freeze for 30 minutes. Top with another pastry layer and spread with the strawberry ice cream. Top with the reserved top pastry layers. Freeze for 30 minutes or until the ice cream is firm. Drizzle with the chocolate topping.

FAST FACT: In 1790, Robert Morris's house at 6th & Market Streets became the Executive Mansion of the United States while Philadelphia served as the temporary capital of the nation. Morris' icehouse was used by President Washington and his household until 1797, and by President John Adams and his family from 1797 to 1800.

Thursday, December 4, 2014

James Monroe, Virginia Spoon Bread, and the Long Winter at Valley Forge

While serving in the Continental Army, James Monroe crossed the Delaware with George Washington, fought at the Battle of Trenton, and endured the long winter at Valley Forge.

While serving in the Continental Army, James Monroe crossed the Delaware with George Washington, fought at the Battle of Trenton, and endured the long winter at Valley Forge. Among the soldiers at Valley Forge were Benedict Arnold, Alexander Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. Another soldier encamped there was Dr. Albigence Waldo, a surgeon from Connecticut, whose diary provides perhaps the best account we have of conditions that winter at Valley Forge:

Dec. 21st., Preparations made for hutts. Provision Scarce...sent a Letter to my Wife. Heartily wish myself at home, my Skin & eyes are almost spoiled with continual smoke. A general cry thro' the Camp this Evening among the Soldiers, "No Meat !, No Meat !", the Distant vales Echo'd back the melancholly sound, "No Meat ! No Meat !"…What have you for our Dinners Boys?" Nothing but Fire Cake & Water, Sir." At night, "Gentlemen the Supper is ready." What is your Supper, Lads? " Fire Cake & Water, Sir..."

Dec. 22nd., Lay excessive Cold & uncomfortable last Night, my eyes are started out from their Orbits like a Rabbit's eyes, occation'd by a great Cold, and Smoke. What have you got for Breakfast, Lads ? " Fire Cake & Water, Sir." I am ashamed to say it, but I am tempted to steal Fowls if I could find them, or even a whole Hog, for I feel as if I could eat one…But why do I talk of hunger & hard usage, when so many in the World have not even fire Cake & Water to eat...

After the war, Monroe returned to Virginia and studied law under Thomas Jefferson, then served as governor of Virginia and was later appointed as U.S. Minister to France. Like Jefferson, Monroe developed a fondness for fancy French cuisine, but historians say that he retained a boyhood taste for Spoon Bread and other simple foods of his Virginia youth.

Because it has a consistency similar to pudding, Spoon Bread is usually served straight from the baking pan with a large spoon. If you'd like to whip up a batch today, here's a quick and simple recipe to try:

¾ cup cornmeal

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup water

3 tablespoons melted butter

2 eggs

1 cup milk

2 teaspoons baking powder

Combine cornmeal and salt in a mixing bowl. Gradually add boiling water. Stir in melted butter.

In a small mixing bowl, beat eggs and milk. Add egg and milk mixture to the cornmeal mixture. Add baking powder and mix.

Pour into a greased baking dish. Bake at 350° for about 30 minutes, until set and lightly browned. Serve straight from the baking dish with a spoon and enjoy!

FAST FACT: In Emmanuel Luetz’s famous painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” James Monroe is depicted directly behind Washington, holding an American flag up against the storm. Measuring 12 feet high and 21 feet long, it's on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Monday, June 30, 2014

The Road to Independence: From the Sugar Act to the Boston Tea Party

So did you know that sugar, coffee, tea and other basic foods played a role in some of the key events that led to the American Revolutionary War? Because volumes could be written about each of these events, I decided to compile a timeline to make this fascinating part of food history a bit easier to digest:

1760 - King George III ascends to the British throne.

1763 - The Treaty of Paris is signed ending the French and Indian War. Part of the Seven Years War between France and England, the French and Indian War was fought in North America between 1754 and 1763. Although victorious, the war plunged Britain deeply into debt, which King George III decided to pay off by imposing taxes on the colonies.

1764 - On April 5, the British Parliament passed the Sugar Act which lowered the rate of tax placed on molasses but increased taxes placed on sugar, coffee, and certain kinds of wines. At the time, most colonists agreed that Parliament had the right to regulate trade, as it had done with the Molasses Act of 1733. But the Sugar Act was specifically aimed at raising revenue which was to be used to pay for the maintenance of British troops stationed in the colonies. Although most colonists were accustomed to being taxed by their own assemblies, they strongly objected to being taxed by Parliament, where they were not represented. It was during protests over the Sugar Act that the famous cry, "No taxation without representation" was often heard.

1765 - In May, the Quartering Act was passed which required colonists to house British troops and supply them with food.

1765 - On March 22, Parliament passed the Stamp Act which placed a tax on newspapers, pamphlets, contracts, playing cards, and other products that were printed on paper. Unlike the Sugar Act which was an external tax (e.g., it taxed only goods imported into the colonies), the Stamp Act was an internal tax levied directly upon the property and goods of the colonists. The Stamp Act forced the colonists to further consider the issue of Parliamentary taxation without representation. United in opposition, colonists convened in October at the Stamp Act Congress in New York and called for a boycott on British imports.

1766 - Bowing to the pressure, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, but, on the same day, passed the Declaratory Act which asserted Parliament's authority to make laws binding on the colonists “in all cases whatsoever.”

1767 - A series of laws known as the Townshend Acts are passed which impose taxes on glass, paint, tea, and other imports into the colonies. One of the most influential responses to the Acts was a series of essays by John Dickinson entitled, "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania." Articulating ideas already widely accepted in the colonies, Dickinson argued that there was no difference between "external" and "internal" taxes, and that any taxes imposed on the colonies by Parliament for the sake of raising a revenue were unconstitutional.

1768 - British troops arrive in Boston to enforce custom laws.

1770 - On March 5, four colonists are shot and killed by British troops stationed in Boston. Patriots label the event “The Boston Massacre.”

1773 - In an effort to save the struggling British East India Company, Parliament passed the Tea Act. This act did not place any new taxes on tea. Instead, it eliminated tariffs placed on tea entering England and allowed the company to sell tea directly to colonists rather than merchants. These changes lowered the price of British tea to below that of smuggled tea, which the British hoped would help end the boycott.

1773 - On December 16, a group of colonists led by Samuel Adams disguised themselves as Mohawk Indians and boarded three British ships that were docked in Boston Harbor. Armed with axes and tomahawks, the men chopped open the crates they found onboard and dumped almost 10,000 pounds of British tea into the harbor. As news of the "Boston Tea Party" spread, patriots in other colonies staged similar acts of resistance.

1774 - In retaliation, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts which closed Boston Harbor to commerce until the colonists had paid for the lost tea, drastically reduced the powers of self-government in the colonies, and provided for the quartering of British troops in the colonists' houses and barns. On September 5, the First Continental Congress convenes in Philadelphia.

1775 - Shots are fired at Lexington and Concord. George Washington takes command of the Continental Army.

1776 - On July 4, the Declaration of Independence is approved. British forces arrive in New York harbor bent on crushing the American rebellion.

Saturday, October 26, 2013

Dolley Madison's Wednesday Squeezes

When James Madison and his wife Dolley moved into the President's House, the room that Thomas Jefferson had used as an office became the State Dining Room. The adjacent parlor (today’s Red Room) was "redecorated in sunflower yellow, with sofas and chairs to match" and "outfitted with a piano, a guitar, and a portrait of Dolley.” One room over, the smaller but more formal elliptical salon was "decorated in the Grecian style" with cream-colored walls.

Together, these three rooms with their interconnecting doors became the venue for Dolley Madison’s legendary “Drawing Rooms,” or "Wednesday Squeezes," which often attracted as many as three hundreds guests and were the most popular social event in town!

Dressed in brightly colored satins or silks and often donning a feathered headpiece or bejeweled turban, Dolley cheerfully greeted and mingled with guests as they enjoyed a festive evening of refreshments, music, and lively conversation. Mrs. Madison also presided over elaborate dinner parties where she delighted guests with such unusual dessert items as pink pepperment ice cream baked in warm pastries.

The Madisons continued to entertain this way until "their brilliant social whirlwind" went up in flames during the War of 1812. On August 24, 1814, while James was away getting a report on the war, Dolley was supposedly awaiting forty dinner guests. Around three o’clock, word was received that British troops had defeated American forces at nearby Blandensburg and were marching toward the capital.

Before fleeing to safety, Dolley quickly gathered what she could, including important documents of her husband’s and Gilbert Stuart’s famous portrait of George Washington. When British soldiers entered the Executive Mansion later that day, they supposedly devoured the lavish dinner that had been left behind. They then piled up furniture, scattered oil-soaked rags in all of the rooms, and lit the President’s House afire!

Although the British quickly evacuated the capital, the months that followed were not happy ones for the Madisons. Many Americans criticized them for abandoning the President’s House and for “allowing the destruction of the most visible symbol of the young republic.”

At their temporary residence, Dolley started up her Wednesday Squeezes again, but “the spirit was gone.” Then came word of General Andrew Jackson’s victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans and the mood of the country was again jubilant. Although a peace treaty had been signed weeks earlier, the Battle of New Orleans transformed “Mr. Madison’s War” (which had been condemned until then as an unnecessary folly) into “a glorious reaffirmation of American independence.”

Source: The President's Table: Two Hundred Years of Dining and Diplomacy (NY, Harper Collins: 2007)

Credit: Dolley Madison, oil on canvas, by Gilbert Stuart

Friday, December 9, 2011

James Monroe, the Long Winter at Valley Forge, and Virginia Spoon Bread

So did you know that while serving in the Continental Army, James Monroe crossed the Delaware with George Washington, fought at the Battle of Trenton, and endured the long winter at Valley Forge? Among the patriots encamped there were Benedict Arnold, Alexander Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall.

So did you know that while serving in the Continental Army, James Monroe crossed the Delaware with George Washington, fought at the Battle of Trenton, and endured the long winter at Valley Forge? Among the patriots encamped there were Benedict Arnold, Alexander Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. Another soldier there was Dr. Albigence Waldo, a surgeon from Connecticut,

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

James Madison, the Potomac Oyster Wars, and the Constitutional Convention

So you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly goes:

So you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly goes: In the seventeenth century, watermen in Maryland and Virginia battled over ownership rights to the Potomac River. Maryland traced its rights to a 1632 charter from King Charles I which included the river. At the same time, Virginia laid its claims to the river to an earlier charter from King James I and a 1688 patent from King James II, both of which also included the river.

In 1776, after more than a century of conflict, Virginia ceded ownership of the river but reserved the right to “the free navigation and use of the rivers Potowmack and Pocomoke." Maryland rejected this reservation and quickly passed a resolution asserting total control over the Potomac. After the Revolution, battles over the river intensified between watermen from both states.

To resolve this problem, leaders from Maryland and Virginia appointed two groups of commissioners which, at the invitation of George Washington, met at Mount Vernon in May of 1785. James Madison led the Virginia contingent and Samuel Chase led the Maryland delegation. Their discussions led to the Compact of 1785, which allowed oystermen from both states free use the river.

Peace prevailed until the supply of oysters began to dwindle, at which point Maryland re-imposed harvesting restrictions. Virginia retaliated by closing the mouth of the Chesapeake and watermen from both states engaged in bloody gun battles which lasted, with periodic breaks, for more than a century.

Today, these battles are known as the Potomac Oyster Wars. They are important in their own right, but they have a larger historical significance because they revealed one of the main weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which was that the federal government didn't have the power to control commerce among the states, a setup that was creating constant chaos and conflict.

With this problem in mind, Madison and the others who convened at Mt. Vernon in May of 1785 agreed to meet the following year at Annapolis to discuss the need for a stronger federal government. Not many delegates showed up and so they agreed to convene the following May in Philadelphia, which is, of course, where the Constitution was drafted.

And so NOW you know how James Madison and a little bivalve from the Potomac helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention!

FACT: Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government didn't have the power to raise its own army, regulate commerce between the states, or coin money for the country. To pass a law, Congress needed the approval of nine out of the 13 states, and in order to amend the Articles it needed the approval of all 13 states, which made it nearly impossible to get anything done! The Articles also didn't provide for an Executive or Judicial branch so there was no separation of powers.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Dolley Madison's Wednesday Squeezes

When James Madison and his wife Dolley moved into the President's House, the room that Thomas Jefferson had used as an office became the State Dining Room. The adjacent parlor (today’s Red Room) was "redecorated in sunflower yellow, with sofas and chairs to match" and "outfitted with a piano, a guitar, and a portrait of Dolley.” One room over, the smaller but more formal elliptical salon was "decorated in the Grecian style" with cream-colored walls.

When James Madison and his wife Dolley moved into the President's House, the room that Thomas Jefferson had used as an office became the State Dining Room. The adjacent parlor (today’s Red Room) was "redecorated in sunflower yellow, with sofas and chairs to match" and "outfitted with a piano, a guitar, and a portrait of Dolley.” One room over, the smaller but more formal elliptical salon was "decorated in the Grecian style" with cream-colored walls. Together, these three rooms with their interconnecting doors became the venue for Dolley Madison’s legendary “Drawing Rooms,” or "Wednesday Squeezes," which often attracted as many as three hundreds guests and were the most popular social event in town!

Dressed in brightly colored satins or silks and often donning a feathered headpiece or bejeweled turban, Dolley cheerfully greeted and mingled with guests as they enjoyed a festive evening of refreshments, music, and lively conversation. Mrs. Madison also presided over elaborate dinner parties where she delighted guests with such unusual dessert items as pink pepperment ice cream baked in warm pastries.

The Madisons continued to entertain this way until "their brilliant social whirlwind" went up in flames during the War of 1812. On August 24, 1814, while James was away getting a report on the war, Dolley was supposedly awaiting forty dinner guests. Around three o’clock, word was received that British troops had defeated American forces at nearby Blandensburg and were marching toward the capital.

Before fleeing to safety, Dolley quickly gathered what she could, including important documents of her husband’s and Gilbert Stuart’s famous portrait of George Washington. When British soldiers entered the Executive Mansion later that day, they supposedly devoured the lavish dinner that had been left behind. They then piled up furniture, scattered oil-soaked rags in all of the rooms, and lit the President’s House afire!

Although the British quickly evacuated the capital, the months that followed were not happy ones for the Madisons. Many Americans criticized them for abandoning the President’s House and for “allowing the destruction of the most visible symbol of the young republic.”

At their temporary residence, Dolley started up her Wednesday Squeezes again, but “the spirit was gone.” Then came word of General Andrew Jackson’s victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans and the mood of the country was again jubilant. Although a peace treaty had been signed weeks earlier, the Battle of New Orleans transformed “Mr. Madison’s War” (which had been condemned until then as an unnecessary folly) into “a glorious reaffirmation of American independence.”

Source: Barry Landau, The President's Table: Two Hundred Years of Dining and Diplomacy (NY, Harper Collins: 2007)

Credit: Dolley Madison, oil on canvas, by Gilbert Stuart

Sunday, July 18, 2010

Sarah Polk and "Hail to the Chief!"

So did you know that the song “Hail to the Chief" didn't originate as a salute to the president? The phrase dates back to a poem by Sir Walter Scott called “The Lady of the Lake.” Published in 1812, the poem was so popular in England that it was adapted into a musical play which later made its way to the United States.

The first time the song was played to honor an American president was at a ceremony in Boston in 1815 to commemorate George Washington's birthday. Andrew Jackson was the first living president to be honored by "Hail to the Chief" on January 9, 1829. The song was also played at Martin Van Buren's inauguration ceremonies on March 4, 1837 and at other social occasions during his administration.

According to historians at the Library of Congress, Julia Tyler, the wife of John Tyler, was the first to specifcially request that the song be played to announce the president’s arrival at an official function. But it was Sarah Polk who requested that the song be routinely played for presidential entrances.

According to White House historian William Seale, Mrs. Polk was concerned that her husband James "was not an impressive figure, so some announcement was necessary to avoid the embarrassment of his entering a crowded room unnoticed. At large affairs the band...rolled the drums as they played the march...and a way was cleared for the President."

If you've never heard them, here are the original lyrics for the American version of the tune:

Hail to the Chief we have chosen for the nation,

Hail to the Chief! We salute him, one and all.

Hail to the Chief, as we pledge co-operation

In proud fulfillment of a great, noble call.

Yours is the aim to make this grand country grander,

This you will do, that's our strong, firm belief.

Hail to the one we selected as commander,

Hail to the President! Hail to the Chief!

In 1954, the Department of Defense recognized "Hail to the Chief" as the official musical tribute for presidential events. Today, the song, along with its preceding fanfare known as "Ruffles and Flourishes," is played by the U.S. Marine Band to announce the arrival of the President at State Dinners and other formal events.

The first time the song was played to honor an American president was at a ceremony in Boston in 1815 to commemorate George Washington's birthday. Andrew Jackson was the first living president to be honored by "Hail to the Chief" on January 9, 1829. The song was also played at Martin Van Buren's inauguration ceremonies on March 4, 1837 and at other social occasions during his administration.

According to historians at the Library of Congress, Julia Tyler, the wife of John Tyler, was the first to specifcially request that the song be played to announce the president’s arrival at an official function. But it was Sarah Polk who requested that the song be routinely played for presidential entrances.

According to White House historian William Seale, Mrs. Polk was concerned that her husband James "was not an impressive figure, so some announcement was necessary to avoid the embarrassment of his entering a crowded room unnoticed. At large affairs the band...rolled the drums as they played the march...and a way was cleared for the President."

If you've never heard them, here are the original lyrics for the American version of the tune:

Hail to the Chief we have chosen for the nation,

Hail to the Chief! We salute him, one and all.

Hail to the Chief, as we pledge co-operation

In proud fulfillment of a great, noble call.

Yours is the aim to make this grand country grander,

This you will do, that's our strong, firm belief.

Hail to the one we selected as commander,

Hail to the President! Hail to the Chief!

In 1954, the Department of Defense recognized "Hail to the Chief" as the official musical tribute for presidential events. Today, the song, along with its preceding fanfare known as "Ruffles and Flourishes," is played by the U.S. Marine Band to announce the arrival of the President at State Dinners and other formal events.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

"When Thomas Jefferson Dined Alone"

A scholar, author, architect, scientist and statesman, Thomas Jefferson applied his brilliant mind to many activities. He was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses when he was only 25, served in the Continental Congress, was governor of Virginia, and a diplomat in France where he helped negotiate the treaties that ended the Revolutionary War.

A scholar, author, architect, scientist and statesman, Thomas Jefferson applied his brilliant mind to many activities. He was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses when he was only 25, served in the Continental Congress, was governor of Virginia, and a diplomat in France where he helped negotiate the treaties that ended the Revolutionary War. He also founded the University of Virginia, was fluent in six languages, including Latin, French, Spanish, Italian and Greek, and wrote the Declaration of Independence at the age of 33! He then served as Secretary of State under George Washington, as Vice President under John Adams, and, along with his good pal James Madison, wrote the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions in defense of states’ rights and the freedom of speech.

During his presidency, Jefferson did many more important things: he repealed the Alien and Sedition Acts, eliminated an unpopular whiskey tax, and sent our navy to fight Barbary pirates who were harassing American ships on the Mediterranean Sea. He also doubled the size of the country by purchasing the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon in 1803 and then commissioned Lewis and Clark to explore western lands which, back then, to most Americans, were totally unknown.

It’s no wonder then that at a Nobel Prize dinner held at the White House in 1962, President John F. Kennedy joked that so many brilliant minds had never been gathered together at the White House "with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone."

Friday, July 16, 2010

James Madison, the Potomac Oyster Wars and the Constitutional Convention

So you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly goes:

So you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly goes: In the seventeenth century, watermen in Maryland and Virginia battled over ownership rights to the Potomac River. Maryland traced its rights to a 1632 charter from King Charles I which included the river. At the same time, Virginia laid its claims to the river to an earlier charter from King James I and a 1688 patent from King James II, both of which also included the river.

In 1776, after more than a century of conflict, Virginia ceded ownership of the river but reserved the right to “the free navigation and use of the rivers Potowmack and Pocomoke." Maryland rejected this reservation and quickly passed a resolution asserting total control over the Potomac. After the Revolution, battles over the river intensified between watermen from both states.

To resolve this problem, leaders from Maryland and Virginia appointed two groups of commissioners which, at the invitation of George Washington, met at Mount Vernon in May of 1785. James Madison led the Virginia contingent and Samuel Chase led the Maryland delegation. Their discussions led to the Compact of 1785, which allowed oystermen from both states free use the river.

Peace prevailed until the supply of oysters began to dwindle, at which point Maryland re-imposed harvesting restrictions. Virginia retaliated by closing the mouth of the Chesapeake and watermen from both states engaged in bloody gun battles which lasted, with periodic breaks, for more than a century.

Today, these battles are known as the Potomac Oyster Wars. They are important in their own right, but they have a larger historical significance because they revealed one of the main weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which was that the federal government didn't have the power to control commerce among the states, a setup that was creating constant chaos and conflict.

With this problem in mind, Madison and the others who convened at Mt. Vernon in May of 1785 agreed to meet the following year at Annapolis to discuss the need for a stronger federal government. Not many delegates showed up and so they agreed to convene the following May in Philadelphia, which is, of course, where the Constitution was drafted.

And so NOW you know how James Madison and a little bivalve from the Potomac helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention!

FACT: Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government didn't have the power to raise its own army, regulate commerce or coin money for the country. To pass a law, Congress needed the approval of nine out of the 13 states, and in order to amend the Articles it needed the approval of all 13 states, which made it nearly impossible to get anything done. The Articles also didn't provide for an Executive or Federal branch so there was no separation of powers.

Credit: Portrait of James Madison by Gilbert Stuart

Thursday, July 8, 2010

George Washington Glazed Baked Ham

According to historians at Mount Vernon, Martha Washington carefully supervised the preparation of the hams and bacon that were eaten by their many guests. Of all the food produced at Mount Vernon it is said that Martha was “especially proud of her hams.”

According to historians at Mount Vernon, Martha Washington carefully supervised the preparation of the hams and bacon that were eaten by their many guests. Of all the food produced at Mount Vernon it is said that Martha was “especially proud of her hams.”After slaughtering and butchering the hogs in December and January, slaves smoked the meat over a fire pit in the smokehouse to preserve it for eating during the coming year. After smoking, the meat was aged and stored in the smokehouse.

Occasionally a thief would break into the smokehouse at night and steal a ham. However, the most notable “ham theft” supposedly occurred in broad daylight, right off the Washingtons' dining room table. The thief was a hound named Vulcan, who “made a running pass at the table and dashed out the door with the savory prize clenched between his teeth.”

A chase ensued, and the ham was recovered but nobody wanted to eat it after that! Although Martha was said to be furious, George reportedly thought the incident was very funny and “delighted in recounting it to guests.”

When preparing this recipe for Glazed Baked Ham, it's best to make the marinade the night before or early in the morning and let the ham marinate for several hours in the refrigerator.

1/3 cup light brown sugar, packed

1/2 cup honey

1/3 cup dry red wine

1/2 cup pineapple juice

1 fully cooked ham, about 6 pounds

In a large bowl, combine the brown sugar, honey, wine, and pineapple juice. Place the ham in the marinade, turn to coat well, and let marinate for 6 hours or overnight in refrigerator.

Preheat the oven to 350°. Place the ham on a rack in a roasting pan, reserving marinade for basting. Bake the ham, basting frequently with the reserved marinade, until a meat thermometer (not touching the bone) reads about 140°, or about 10 minutes per pound.

Thanks for stopping by THE HISTORY CHEF! For a free excerpt of my new book from Simon and Schuster click here!

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

George Washington Garlic Mashed Potatoes

So did you know that by the time he became president, George Washington had lost almost all of his teeth? Because of constant pain constant from ill-fitting dentures, George had to eat soft foods (like mashed potatoes and hoe cakes) throughout most of his adult life.

So did you know that by the time he became president, George Washington had lost almost all of his teeth? Because of constant pain constant from ill-fitting dentures, George had to eat soft foods (like mashed potatoes and hoe cakes) throughout most of his adult life. Contrary to popular belief, George did not wear a set of wooden dentures. Instead, a talented New York dentist named John Greenwood handcrafted his dentures from elephant ivory, hippopotamus tusks and parts of horse and donkey teeth. This recipe for roasted garlic mashed potatoes, taken from Martha Washington's Booke of Cookery, has been adapted for modern cooks.

4 large russet potatoes, peeled and quartered

2 garlic cloves, peeled

2 teaspoons coarse salt

1 stick unsalted butter

¾ cup heavy cream

In a large pot of cold water, bring the potatoes and garlic to a boil. Salt the water and cook until the potatoes are tender, about 20 minutes. Drain and return the potatoes to the pot. Mash over low heat with the butter, cream and 2 teaspoons salt. Serve warm and enjoy!

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

James Monroe Virginia Spoon Bread

While serving in the Continental Army, James Monroe crossed the Delaware with George Washington, fought at the Battle of Trenton, and endured the harsh winter at Valley Forge.

Among the soldiers at Valley Forge were Benedict Arnold, Alexander Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. Another soldier encamped there was Dr. Albigence Waldo, a surgeon from Connecticut, whose diary provides perhaps the best account we have of conditions that winter at Valley Forge:

Dec. 22nd., Lay excessive Cold & uncomfortable last Night, my eyes are started out from their Orbits like a Rabbit's eyes, occation'd by a great Cold, and Smoke. What have you got for Breakfast, Lads ? " Fire Cake & Water, Sir." I am ashamed to say it, but I am tempted to steal Fowls if I could find them, or even a whole Hog, for I feel as if I could eat one…But why do I talk of hunger & hard usage, when so many in the World have not even fire Cake & Water to eat...

After the war, Monroe returned to Virginia and studied law under Thomas Jefferson. He then served as governor of Virginia and was later appointed U.S. Minister to France. Like Jefferson, Monroe developed a fondness for fancy French cuisine but retained a taste for Virginia Spoon Bread and other simple foods of his youth.

Because it has a consistency similar to pudding, Spoon Bread is usually served straight from the baking pan with a large spoon. If you would like to make some, here is a simple recipe to try:

¾ cup cornmeal

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup water

3 tablespoons melted butter

2 eggs

1 cup milk

2 teaspoons baking powder

Combine cornmeal and salt in a mixing bowl. Gradually add boiling water. Stir in melted butter.

In a small mixing bowl, beat eggs and milk. Add egg and milk mixture to the cornmeal mixture. Add baking powder and mix.

Pour into a greased baking dish. Bake at 350° for about 30 minutes, until set and lightly browned. Serve straight from the baking dish with a spoon and enjoy!

By the way, did you know that in Emmanuel Luetz’s painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware” James Monroe is depicted directly behind Washington, holding an American flag up against the storm? If you would like to see this painting (it measures 12 feet high and 21 feet long), it is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Among the soldiers at Valley Forge were Benedict Arnold, Alexander Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. Another soldier encamped there was Dr. Albigence Waldo, a surgeon from Connecticut, whose diary provides perhaps the best account we have of conditions that winter at Valley Forge:

Dec. 22nd., Lay excessive Cold & uncomfortable last Night, my eyes are started out from their Orbits like a Rabbit's eyes, occation'd by a great Cold, and Smoke. What have you got for Breakfast, Lads ? " Fire Cake & Water, Sir." I am ashamed to say it, but I am tempted to steal Fowls if I could find them, or even a whole Hog, for I feel as if I could eat one…But why do I talk of hunger & hard usage, when so many in the World have not even fire Cake & Water to eat...

After the war, Monroe returned to Virginia and studied law under Thomas Jefferson. He then served as governor of Virginia and was later appointed U.S. Minister to France. Like Jefferson, Monroe developed a fondness for fancy French cuisine but retained a taste for Virginia Spoon Bread and other simple foods of his youth.

Because it has a consistency similar to pudding, Spoon Bread is usually served straight from the baking pan with a large spoon. If you would like to make some, here is a simple recipe to try:

¾ cup cornmeal

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup water

3 tablespoons melted butter

2 eggs

1 cup milk

2 teaspoons baking powder

Combine cornmeal and salt in a mixing bowl. Gradually add boiling water. Stir in melted butter.

In a small mixing bowl, beat eggs and milk. Add egg and milk mixture to the cornmeal mixture. Add baking powder and mix.

Pour into a greased baking dish. Bake at 350° for about 30 minutes, until set and lightly browned. Serve straight from the baking dish with a spoon and enjoy!

By the way, did you know that in Emmanuel Luetz’s painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware” James Monroe is depicted directly behind Washington, holding an American flag up against the storm? If you would like to see this painting (it measures 12 feet high and 21 feet long), it is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)