So

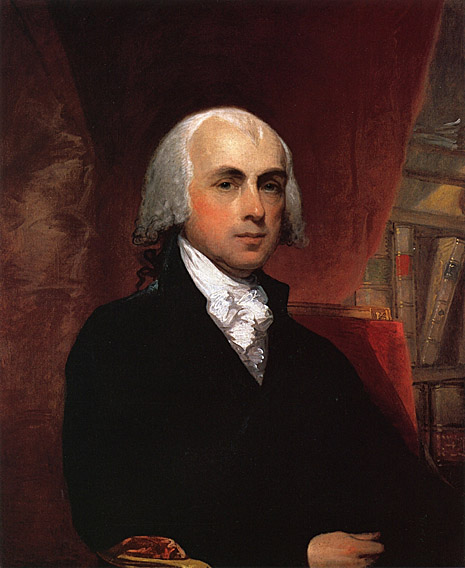

you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the

Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role

in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave

the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly

goes:

So

you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the

Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role

in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave

the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly

goes:In the seventeenth century, watermen in Maryland and Virginia battled over ownership rights to the Potomac River. Maryland traced its rights to a 1632 charter from King Charles I which included the river. At the same time, Virginia laid its claims to the river to an earlier charter from King James I and a 1688 patent from King James II, both of which also included the river.

In 1776, after more than a century of conflict, Virginia ceded ownership of the river but reserved the right to “the free navigation and use of the rivers Potowmack and Pocomoke." Maryland rejected this reservation and quickly passed a resolution asserting total control over the Potomac. After the Revolution, battles over the river intensified between watermen from both states.

To resolve this problem, leaders from Maryland and Virginia appointed two groups of commissioners which, at the invitation of George Washington, met at Mount Vernon in May of 1785. James Madison led the Virginia contingent and Samuel Chase led the Maryland delegation. Their discussions led to the Compact of 1785, which allowed oystermen from both states free use the river.

Peace prevailed until the supply of oysters began to dwindle, at which point Maryland re-imposed harvesting restrictions. Virginia retaliated by closing the mouth of the Chesapeake and watermen from both states engaged in bloody gun battles which lasted, with periodic breaks, for more than a century.

Today, these battles are known as the Potomac Oyster Wars. They are important in their own right, but they have a larger historical significance because they revealed one of the main weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which was that the federal government didn't have the power to control commerce among the states, a setup that was creating constant chaos and conflict.

With this problem in mind, Madison and the others who convened at Mt. Vernon in May of 1785 agreed to meet the following year at Annapolis to discuss the need for a stronger federal government. Not many delegates showed up and so they agreed to convene the following May in Philadelphia, which is, of course, where the Constitution was drafted.

And so NOW you know how James Madison and a little bivalve from the Potomac helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention!

FACT: Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government didn't have the power to raise its own army, regulate commerce between the states, or coin money for the country. To pass a law, Congress needed the approval of nine out of the 13 states, and in order to amend the Articles it needed the approval of all 13 states, which made it nearly impossible to get anything done! The Articles also didn't provide for an Executive or Federal branch so there was no separation of powers.