So did you know that sugar, coffee, tea and other basic foods played a role in some of the key events that led to the American Revolutionary War? Because volumes could be written about each of these events, I decided to compile a timeline to make this fascinating part of food history a bit easier to digest:

1760 - King George III ascends to the British throne.

1763 - The Treaty of Paris is signed ending the

French and Indian War. Part of the Seven Years War between France and England, the French and Indian War was fought in North America between 1754 and 1763. Although victorious, the war plunged Britain deeply into debt, which King George III and the British Parliament decided to pay off by imposing taxes on the colonies.

1764 - On April 5, the Parliament passed the

Sugar Act which lowered the rate of tax placed on molasses but increased taxes placed on sugar, coffee, and certain kinds of wines. At the time, most colonists agreed that Parliament had the right to regulate trade, as it had done with the

Molasses Act of 1733. But the Sugar Act was specifically aimed at raising revenue which was to be used to pay for the maintenance of British troops stationed in the colonies. Although most colonists were accustomed to being taxed by their own assemblies, they strongly objected to being taxed by Parliament, where they were not represented. It was during angry protests over the Sugar Act that the famous cry, "No taxation without representation" was often heard.

1765 - In May, the Quartering Act was passed which required colonists to house British troops and supply them with

food.

1765 - On March 22, Parliament passed the

Stamp Act which placed a tax on newspapers, pamphlets, contracts, playing cards, and other products that were printed on paper. Unlike the Sugar Act which was an external tax (e.g., it taxed only goods imported into the colonies), the Stamp Act was an internal tax levied directly upon the property and goods of the colonists. The Stamp Act forced the colonists to further consider the

issue of Parliamentary taxation without representation. Outraged and united in opposition, patriot leaders convened in October at the Stamp Act Congress in New York and called for a boycott on British imports.

1766 - Bowing to the pressure, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, but, on the same day, passed the

Declaratory Act which asserted Parliament's authority to make laws binding on the colonists “in all cases whatsoever.”

1767 - A series of laws known as the

Townshend Acts are passed which impose taxes on glass, paint, tea, and other imports into the colonies. One of the most influential responses to the Acts was a series of essays by John Dickinson entitled, "

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania." Articulating ideas already widely accepted in the colonies, Dickinson argued that there was no difference between "external" and "internal" taxes, and that any taxes imposed on the colonies by Parliament for the sake of raising a revenue were unconstitutional.

1768 - British warships arrive in Boston Harbor to enforce custom laws. So now there's a bunch of young British soldiers in red coats dragging loaded cannons and guns and thousands of outraged American patriots. WHAT COULD POSSIBLY GO WRONG?

1770 - Nothing too terrible. Until the cold, snowy evening of March 5. That’s when a rowdy crowd of colonists started harassing British soldiers on duty in front of the Custom House in Boston. Tensions intensified as the crowd grew and colonists began throwing snowballs at the soldiers, daring them to open fire.

Then, one British soldier was hit in the face with a stick. Shots rang out. When the smoke cleared, three American colonists were dead, including

Crispus Attucks, a former slave who worked on a whaling ship, and two others later died from their injuries.

Outraged, Sam Adams calls the British soldiers “bloody murderers” and labels the event “The Boston Massacre.”

1773 - After that, British soldiers are ordered to leave Boston. Tensions settle down for a while. But, in 1773, Parliament makes another REALLY. BAD. MOVE. In an effort to save the struggling British East India Company, Parliament passed the

Tea Act. This act did not place any new taxes on tea. Instead, it eliminated tariffs placed on tea entering England and allowed the company to sell tea directly to colonists rather than merchants. These changes lowered the price of British tea to below that of smuggled tea, which the British hoped would help end the boycott. But that's NOT what happened!

1773 - Instead, at around midnight on December 16, a group of colonists led by Samuel Adams disguised themselves as Mohawk Indians and

boarded three British ships that were docked in Boston Harbor. Armed with axes and tomahawks, the men chopped open 342 crates and dumped 46 tons of British tea -- that's the weight of 400 baby elephants! -- into the

harbor. As news of the "

Boston Tea Party" spread, patriots in other colonies staged similar acts of resistance.

1774 - When news of the Boston Tea Party reached London, King George became enraged and threw a fit. Calling it “violent and outrageous,” he viewed it as a complete rejection of British rule, and he vowed to punish Massachusetts swiftly and severely. At the king's request, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts (also called the Intolerable Acts) which closed Boston Harbor to commerce until the colonists had paid for the lost tea, drastically reduced the powers of self-government in the colonies, and provided for the quartering of British troops in the colonists' houses and barns.

At that point, patriot leaders had had enough and agreed to convene in Philadelphia to come up with a plan of action. And, in September, Samuel Adams and his younger cousin John Adams set out from Boston to the first Continental Congress.

Meanwhile, down in Virginia, George Washington was preparing for the Continental Congress, as well. One of the few patriot leaders with military experience (he was a general in the French and Indian War), Washington was widely-respected and committed to the American cause. “If need be,” he promised, “I will raise one thousand men, subsist them at my own expense, and march myself at their head for the relief of Boston.”

It was under these explosive circumstances that the FIRST CONTINENTAL CONGRESS convened in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774.

There were fifty-six delegates from twelve colonies, including Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

After heated debate, the delegates declared the Intolerable Acts to be an illegal violation of the rights of American colonists. They also decided it was time to start boycotting all British imports again. Most important, it was agreed that the colonies should start raising and arming militias (groups of citizen soldiers) should war break out with Britain.

1775 - Now the stage was set for a major showdown, and things started happening fast.

King George announced to Parliament that the colonies were in “a state of rebellion” and that “blows must decide” who would control America.

By early April, 1775, General Gage was in command of an army of 3,000 soldiers in and around Boston, with thousands more on the way.

On April 19, 1775, shots were fired at Lexington and Concord. When the smoke cleared, more than 200 American and British forces had been killed.

In June, 1775, the Second Continental Congress unanimously voted to appoint George Washington as General and Commander-in-Chief of the newly formed Continental Army.

1776 -

Throughout early 1776, some Americans hoped to avoid war with Britain. But, on July 4, 1776, Congress formally approved the Declaration of Independence, and soon, British forces arrived in New York Harbor, bent on crushing the American rebellion!

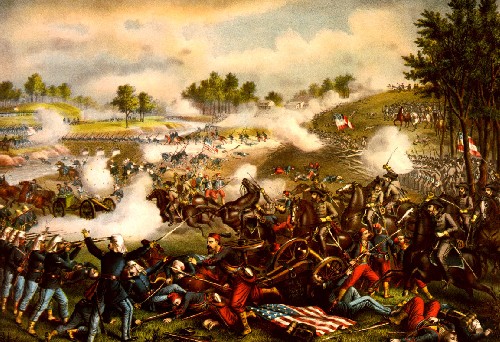

At the end of the Civil War, the South lay in ruins. Southern plantations and entire cities had been destroyed during the war. Without food, many southerners starved to death, and most of those who survived lost just about everything they owned.

As a result, the government had to figure out how to rebuild the South.

At the end of the Civil War, the South lay in ruins. Southern plantations and entire cities had been destroyed during the war. Without food, many southerners starved to death, and most of those who survived lost just about everything they owned.

As a result, the government had to figure out how to rebuild the South.