During the Great Depression, many Americans couldn't afford to pay their mortgages and lost everything they owned. Suddenly homeless, millions of American families had no choice but to find shelter in shanty towns, or Hoovervilles, which sprang up throughout the United States in the early 1930s.

In the popular musical Annie, which takes place in a Hooverville beneath the 59th Street Bridge in New York City, there's a song called “We'd Like to Thank You, Herbert Hoover." In it, the chorus blames President Hoover for all the hardships they've endured as a result of the Great Depression. Maybe you've heard the lyrics:

[ALL]

Today we're living in a shanty

Today we're scrounging for a meal

[SOPHIE]

Today I'm stealing coal for fires

Who knew I could steal?...

[ALL]

We'd like to thank you: Herber Hoover

For really showing us the way

We'd like to thank you: Herbert Hoover

You made us what we are today...

In ev'ry pt he said "a chicken"

But Herbert Hoover he forgot

Not only don't we have the chicken

We ain't got the pot!

In the Election of 1932, Hoover never actually uttered the phrase “a chicken in every pot and two automobiles in every back yard,” but the Republican Party did run ads suggesting that this was what Americans could expect if he was elected.

As far as modern campaign slogans go, "A Chicken in Every Pot" sounds rather modest. But "the words rang hollow during the Great Depression that blighted Hoover's presidency and shook the economic foundations" of the nation to the core. As one observer remarked, daily bread and shoes without holes were hard enough to come by, let alone stewing chickens and automobiles.

Nevertheless, while millions of Americans were scrounging for food in the streets, Hoover and his wife "Lou" were entertaining on a scale not seen at the White House in years. According to historian Poppy Cannon, "The watchword had been economy while the Coolidges lived at the White House. Now it was elegance. Mrs. Hoover never questioned the amount of food consumed or its cost. Her only requirement was that it be of the best quality, well cooked and well served.”

Needless to say, this infuriated many Americans, and, in the Election of 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt won in a massive landslide, ushering in decades of Democratic dominance in presidential elections. Meanwhile, Hoover left the White House in disgrace, "having incurred the public's wrath for failing to lift the nation out of the Great Depression."

Sunday, February 22, 2015

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Civil War Rations and Hardtack Crackers

During the Civil War, rations generally consisted of twelve ounces of bacon or pork or one pound of fresh or salted beef; beans or peas; rice or hominy; sugar, coffee or tea and hard biscuits or crackers known as Hardtack. Hardtack was usually square or rectangular in shape with tiny holes baked into it, similar to the soda crackers we're familiar with today.

During the Civil War, rations generally consisted of twelve ounces of bacon or pork or one pound of fresh or salted beef; beans or peas; rice or hominy; sugar, coffee or tea and hard biscuits or crackers known as Hardtack. Hardtack was usually square or rectangular in shape with tiny holes baked into it, similar to the soda crackers we're familiar with today. According to historians, factories in the north “baked thousands of hardtack crackers every day, packed them in crates, and shipped them out by wagon or rail.” Sometimes the hardtack didn't get to the soldiers until weeks, or even months, after they had been made. By then, the crackers were so hard that soldiers called them "tooth dullers" or "sheet iron crackers."

Older crackers were often infested with maggots or weevils so soldiers referred to them as "worm castles" because of the many holes bored through them by these tiny pests. Civil War soldiers dreaded these crackers so much that they sang a wartime tune about them called “Hard Tack, Come Again No More!” These are some of the lyrics:

Let us close our game of poker, take our tin cups in our hand

As we all stand by the cook's tent door

As dried monies of hard crackers are handed to each man.

O, hard tack, come again no more!

CHORUS: 'Tis the song, the sigh of the hungry:

"Hard tack, hard tack, come again no more."

Many days you have lingered upon our stomachs sore.

O, hard tack, come again no more!

'Tis a hungry, thirsty soldier who wears his life away

In torn clothes - his better days are o'er.

And he's sighing now for whiskey in a voice as dry as hay,

"O, hard tack, come again no more!" - CHORUS

'Tis the wail that is heard in camp both night and day,

'Tis the murmur that's mingled with each snore.

'Tis the sighing of the soul for spring chickens far away,

"O, hard tack, come again no more!" - CHORUS

But to all these cries and murmurs, there comes a sudden hush

As frail forms are fainting by the door,

For they feed us now on horse feed that the cooks call mush!

O, hard tack, come again once more!

'Tis the dying wail of the starving:

"O, hard tack, hard tack, come again once more!"

You were old and very wormy, but we pass your failings o'er.

O, hard tack, come again once more!

Despite the bad rap hardtack got, soldiers prepared it in a number of ways. Some would crumble it into coffee or tea or soften it in water and fry it in bacon grease. Others made a popular dish called "skillygallee" by crumbling the crackers into salted fried pork. If you’d like to whip up some Hardtack today, here's a simple recipe to try from americancivilwar.com:

2 cups of flour

1/2 to 3/4 cup water

1 tablespoon of Crisco or vegetable fat

6 pinches of salt

Mix the ingredients together into a stiff batter, knead several times, and spread the dough out flat to a thickness of 1/2 inch on a non-greased cookie sheet. Bake for one-half an hour at 400 degrees. Remove from oven, cut dough into 3-inch squares, and punch four rows of holes, four holes per row into the dough. Turn dough over, return to the oven and bake another half hour. Turn oven off and leave the door closed. Leave the hardtack in the oven until cool. Remove, eat with coffee or tea and sing "Hardtack, Come Again No More!"

FOOD FACT: According to visitgettysburg.com, rations also consisted of fresh vegetables (sometimes fresh carrots, onions, turnips and potatoes), dried fruit, and dried vegetables when available. Men also "foraged and scavenged the countryside for fresh food at times." Many also received supplements mailed from their family, or they could buy foods from sulters who followed the troops selling pickles, cheese, sardines, cakes, candies, beer and whisky, even though the troops were forbidden to drink alcohol.

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Woodrow Wilson, the Sinking of the Lusitania, and Food Blockades During World War I

On May 7, 1915, a German submarine torpedoed the British passenger liner Lusitania that was en route from New York City to London. Attacked without warning, the ship sank in fifteen minutes, killing 1,198 civilians, including 128 American men, women and children.

On May 7, 1915, a German submarine torpedoed the British passenger liner Lusitania that was en route from New York City to London. Attacked without warning, the ship sank in fifteen minutes, killing 1,198 civilians, including 128 American men, women and children. Woodrow Wilson immediately denounced the sinking of the Lusitania in harsh, threatening terms and demanded that Germany pledge to never launch another attack on citizens of neutral countries, even when traveling on French or British ships. Germany initially acquiesced to Wilson's demand but only temporarily. In March of 1916, a German U-boat torpedoed the French passenger liner Sussex, causing a heavy loss of life and injuring several Americans.

Two months later, in what is known as the Sussex pledge, German officials announced that they would no longer sink Allied merchant ships without warning. At the same time, however, they made it clear that it would resume submarine attacks if the Allies refused to respect international law, which in effect meant that the Allies had to lift their blockades of food and other raw materials bound for the Central powers.

Despite further provocations, President Wilson still hoped for a negotiated settlement until February 1, 1917, when Germany resumed submarine warfare against merchant ships, including those of the United States and other neutral countries. In response, Wilson immediately broke off diplomatic relations with Germany.

Then, on February 25, the British intercepted and decoded a telegram from Germany's foreign secretary Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador in Mexico. The so-called "Zimmermann telegram" proposed that in the event of war with the United States, Germany and Mexico would form an alliance. In return, Germany promised to regain for Mexico its "lost provinces" of Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico.

The release of the Zimmermann Telegram ignited a public furor that was further enflamed by the loss of at least three U.S. merchant ships to German submarines. All hope for neutrality was now lost, and, on April 2, 1917, Wilson appeared before a joint session of Congress and asked for a Declaration of War against Germany.

This is a partial excerpt of what he said:

It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts - for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free. To such a task we dedicate our lives and our fortunes...

Wilson was having lunch in the State Dining Room of the White House when he received word that the Declaration of War had arrived for his signature. Although no one knows what Wilson ate for lunch on that momentous day, we do know that by the time the United States entered the war, German submarines were taking a devastating toll on the supplies of food and other provisions being shipped to Britain from abroad.

In response, the British admiralty decided to establish a system of convoys. Under the plan, merchant ships were grouped together in "convoys" and provided with warship escorts through the most dangerous stretches of the North Atlantic. The convoys had a dramatic effect. By the end of 1917, the tonnage of Allied shipping lost each month to German U-boat attacks plummeted from one million tons in April to about 350,000 tons in December.

And although many other critical factors were at play, the increase in food and other necessary wartime provisions helped to stiffen the resolve of French and British troops and thwarted Germany’s attempt to force Britain’s surrender.

Monday, February 16, 2015

Franklin Roosevelt, World War II, and "There's Not Enough Milk for the Babies"

On February 19, 1942, just two and a half months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which led to the internment of more than 125,000 Japanese-American citizens who were forcibly removed from their homes and detained in internment camps on the West Coast until the end of World War II.

On February 19, 1942, just two and a half months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which led to the internment of more than 125,000 Japanese-American citizens who were forcibly removed from their homes and detained in internment camps on the West Coast until the end of World War II. The daily conditions of camp life are especially vivid in pictures and descriptions of the mass feeding of thousands of Japanese men, women and children. On May 11, 1942, Joseph Conrad of the American Friends Service Committee submitted a Progress Report to the federal government which read:

There's not enough milk for the babies in camp because the Army's contract for milk is with farmers in Oregon and even though there is plenty of milk in the neighboring towns begging to be used, red tape makes it impossible.

There hasn't been enough food to go around because there were [more] arrivals than were expected. Some have gone without meals several times. There has been no fresh vegetables; no fruit (and a large part of the population are children), no fresh meat, but plenty of canned food for those who were early in line to get it...

Meanwhile, as thousands of interned children were suffering from malnutrition, millions of homeless and unemployed Americans were starving during the Great Depression. To address this national crisis, Soup Kitchens began opening in large cities and small towns throughout the United States.

When soup kitchens first appeared, they were generally run by churches or private charities. But by the mid-1930s, when Roosevelt was in office, state and federal governments were also operating them.

Why soup? Throughout history, soup has been one of the primary foods consumed by poor and homeless people. If you think about it, this makes sense because soup is economical (it can be prepared with whatever scraps of food are available and can be stretched to feed more people by adding water). It is also quick and simple to make (only a pot is needed) and easy to serve (it requires only a bowl and spoon, or, in a pinch, can be sipped).

There was never such a family for soups as the Roosevelts. All the years they occupied the White House we kept the big steel soup kettles singing in the White House - clear soup for dinner and cream soup for lunch. Pretty nearly every usable variety of fish, fowl, beast, mineral, vegetable, and contiment was used in our White House soups...

Give Mrs. Roosevelt a bowl of soup and a dish of fruit for lunch and she'd be off with recharged vitality on one of her trips...Cream of almond - L'Amande soup - was one of her special favorites. The President was partial to fish soups... Among the recipes his mother gave me was the one for clam chowder...Another of his favorites was the green turtle soup, and there was always a great fuss when it was made.

Today, green turtle soup is prohibited in the United States because most species of sea turtles are considered threatened or endangered. But you can try this simple and economical recipe for Chicken Rice Soup from the Food Network courtesy of Ree Drummond or this one for Creamy Chicken Soup:

.

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 tablespoons all-purpose flour

4 cups chicken stock

2 cups heavy cream

2 egg yolks, beaten

coarse Salt, to taste

fresh ground black pepper, to taste

2 cups diced cooked boneless, skinless, chicken breast

chopped fresh parsley

Add unsalted butter to stockpot. Melt over low heat. Stir in flour, and stir constantly for 2 minutes. Gradually stir in chicken stock. Heat over medium heat, almost but not boil. Add heavy cream and egg yolks to medium bowl. Whisk to combine. Ladle in ½ cup hot soup. Blend with whisk. Stir cream mixture into stockpot.Season with coarse salt and fresh ground black pepper. Add chicken meat and Simmer until heated through but not boiling. Serve hot in individual soup bowls. Garnish with chopped parsley.

FOOD FACT: In a 1942 New Republic article, Ted Nakashima described the daily conditions of camp life this way: The food and sanitation problems are the worst. We have had absolutely no fresh meat, vegetables or butter since we came here. Mealtime queues extend for blocks; standing in a rainswept line, feet in the mud, waiting for the scant portions of canned wieners and boiled potatoes, hash for breakfast or canned wieners and beans for dinner. Milk only for the kids. Coffee or tea dosed with saltpeter and stale bread are the adults' staples.

Thursday, February 12, 2015

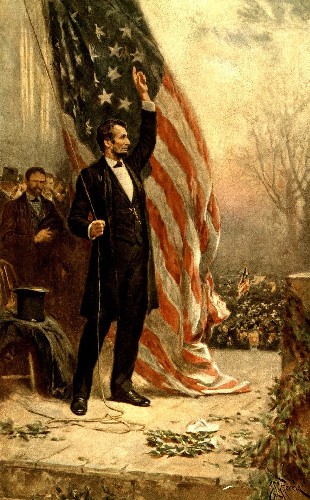

Abraham Lincoln Chicken Fricassee

Despite the exigencies of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln took his social duties at the White House seriously, and if the only culinary records of his administration were the menus of his lavish state banquets and balls, one could justifiably conclude that he was "a gourmet to end gourmets, a connoisseur of exquisite sensitivity [and] a bon vivant supreme."

But nothing could be further from the truth. Not prone to eating breakfast every day, it has been said that Abe had an egg and biscuit only occasionally. Lunch was often only an apple with a glass of milk, and "dinner could be entirely forgotten" unless a tray of food was forced on him. “Abe can sit and think longer without food than any other person I have ever met,” Lincoln’s former law partner in Chicago wrote. And Lincoln’s sister-in-law recalled, “He loved nothing and ate mechanically. I have seen him sit down at the table and never unless recalled to his senses, would he think of food.”

But when Lincoln did turn his attention to food, he ate heartily and never lost a boyhood taste for Kentucky Corn Cakes, Gooseberry Cobbler, Rail Splitters, Gingerbread Cookies, and Corn Dodgers. And it has been said that one of the few entrees that would tempt Lincoln was Chicken Fricassee.

According to A Treasury of White House Cooking by Francois Rysavy, Lincoln "liked the chicken cut up in small pieces, fried with seasonings of nutmeg and mace and served with a gravy made of the chicken drippings."Although Abe's favorite recipe for Chicken Fricassee has surely been lost to posterity, you can try this more recent one for Tarragon Chicken Fricassee from epicurious.com and this one Gourmet Magazine:

3 1/2 to 4 pounds chicken pieces with skin and bone

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1/2 cup finely chopped shallots

1 garlic clove, finely chopped

1 Turkish or 1/2 California bay leaf

1/2 cup dry white wine

1 cup heavy cream

1/2 cup reduced-sodium chicken broth

1 1/2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh tarragon

1/4 teaspoon fresh lemon juice

Pat chicken dry and sprinkle all over with salt and pepper. Heat oil in heavy skillet over moderately high heat until hot, then sauté chicken in 2 batches, skin side down first, turning over once, until browned, 10 to 12 minutes total per batch. Transfer to a plate.

Pour off all but 2 tablespoons oil from skillet, then cook shallots, garlic, and bay leaf over moderate heat, stirring occasionally, until shallots are softened, about 2 minutes. Add wine and bring to a boil. Stir in cream, broth, and 1 tablespoon tarragon, then add chicken, skin side up, and simmer, covered, until just cooked through, 20 to 25 minutes. Transfer chicken with tongs to a platter and keep warm, loosely covered. If necessary, boil sauce until thickened slightly. Stir in lemon juice, remaining 1/2 tablespoon tarragon, and salt and pepper to taste. Discard bay leaf; pour sauce over chicken.

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

George Washington, the Battle of the Chesapeake, and the Significance of Food in Military History

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes, was a critical naval battle in the Revolutionary War. It also provides a fabulous example of how world and military history have been shaped in part by food.

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes, was a critical naval battle in the Revolutionary War. It also provides a fabulous example of how world and military history have been shaped in part by food. The battle took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake on September 5, 1781 between a British fleet led by Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves and a French fleet led by Rear Admiral François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse. Although it didn't end the war, the victory by the French was a major strategic defeat for the British because it prevented the Royal Navy from resupplying food, troops, and other provisions to General Charles Cornwallis’ blockaded forces at Yorktown.

Equally important, it prevented interference with the delivery of provisions that were en route to General George Washington's army through the Chesapeake. Six weeks later, with the British forces trapped, hungry and depleted, Cornwallis surrendered his army to George Washington after the Seige at Yorktown, which effectively ended the war and forced Great Britain to later recognize the independence of the United States.

Of course, many other critical factors contributed to the end of the war, but that doesn't diminish the fact that food (or the lack of it) has played an enormously important role in the course of world and military history.

FAST FACT: General Winfield Scott observed that, "The movements of an army are necessarily subordinate...to considerations of the belly." And Napoleon valued pickles as a food source for his armies so much that he offered the equivalent of $250,000 to the first person who discovered a way to safely preserve food. The man who won the prize in 1809 was a French chef and confectioner named Nicolas Appert who discovered that food wouldn’t spoil if you removed the air from a bottle and boiled it long enough. This process, of course, is known as canning and Appert's discovery was one of the most pivotal events in the modern history of food and human nutrition!

Monday, February 9, 2015

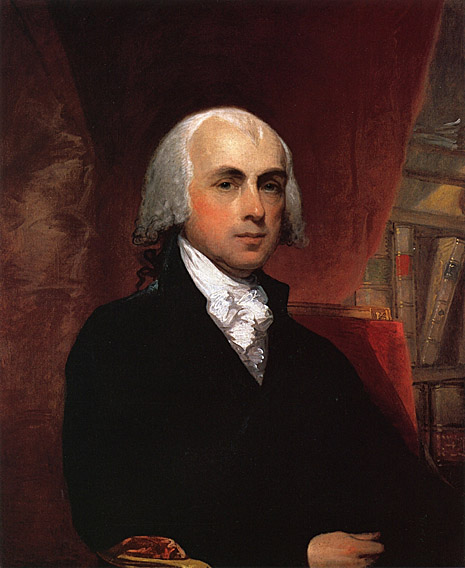

James Madison, the Potomac Oyster Wars, and the Path to the Constitutional Convention

So

you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the

Bill of Rights. But what you might not know is that he also played a major role

in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars, which helped pave

the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly

goes:

So

you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the

Bill of Rights. But what you might not know is that he also played a major role

in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars, which helped pave

the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly

goes:In the seventeenth century, watermen in Maryland and Virginia battled over ownership rights to the Potomac River. Maryland traced its rights to a 1632 charter from King Charles I which included the river. At the same time, Virginia laid its claims to the river to an earlier charter from King James I and a 1688 patent from King James II, both of which also included the river.

In 1776, after more than a century of conflict, Virginia ceded ownership of the river but reserved the right to “the free navigation and use of the rivers Potowmack and Pocomoke." Maryland rejected this reservation and quickly passed a resolution asserting total control over the Potomac. After the Revolution, battles over the river intensified between watermen from both states.

To resolve this problem, leaders from Maryland and Virginia appointed two groups of commissioners which, at the invitation of George Washington, met at Mount Vernon in May of 1785. James Madison led the Virginia contingent and Samuel Chase led the Maryland delegation. Their discussions led to the Compact of 1785, which allowed oystermen from both states free use the river.

Peace prevailed until the supply of oysters began to dwindle, at which point Maryland re-imposed harvesting restrictions. Virginia retaliated by closing the mouth of the Chesapeake and watermen from both states engaged in bloody gun battles which lasted, with periodic breaks, for more than a century.

Today, these battles are known as the Potomac Oyster Wars. They're important in their own right but they have a larger historical significance because they revealed one of the main weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which was that the federal government didn't have the power to control commerce among the states, a setup that was creating constant chaos and conflict.

With this problem in mind, Madison and the others who convened at Mt. Vernon in May of 1785 agreed to meet the following year at Annapolis to discuss the need for a stronger federal government. Not many delegates showed up and so they agreed to convene the following May in Philadelphia, which is, of course, where the Constitution was drafted.

And so NOW you know how James Madison and a little bivalve from the Potomac helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention!

FAST FACT: Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government didn't have the power to raise an army, regulate interstate commerce, or coin money for the country. To pass a law, Congress needed the approval of nine out of the 13 states, and in order to amend the Articles it needed the approval of all 13 states, which made it nearly impossible to get anything done! The Articles also didn't provide for an Executive or Federal branch so there was no separation of powers.