From all accounts, the dinner parties hosted by James and Elizabeth Monroe were very formal affairs. Large dinners had an especially “cold air,” according to novelist James Fenimore Cooper, who was frequently invited to dine at the Monroe White House. Describing a particular dinner, Cooper wrote:

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Great Depression, and the Thanksiving Day Date-Change Fiasco

So did you know that in 1939 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt decided to move the Thanksgiving Day holiday forward by a week? Rather than allow it to fall on its traditional date, the last Thursday of November, Roosevelt issued a proclamation declaring that the holiday would instead be celebrated one week earlier.

So did you know that in 1939 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt decided to move the Thanksgiving Day holiday forward by a week? Rather than allow it to fall on its traditional date, the last Thursday of November, Roosevelt issued a proclamation declaring that the holiday would instead be celebrated one week earlier. Why did he make such a seemingly random decision in the midst of the Great Depression? Well, his reasons were rooted in economic concerns and he hoped that by moving Thanksgiving forward it would bolster the struggling economy by extending the Christmas shopping season by a week. According to the Wall Street Journal:

There were five Thursdays in November that year, which meant that Thanksgiving would fall on the 30th. That left just 20 shopping days till Christmas. By moving the holiday up a week to Nov. 23, Roosevelt hoped to give the economy a lift by allowing shoppers more time to make their holiday purchases and —so his theory went—spend more money.

In an informal news conference in August announcing his decision, FDR offered a little tutorial on the history of the holiday. Thanksgiving was not a national holiday, he noted, meaning that it was not set by federal law. According to custom, it was up to the president to pick the date every year. It was not until 1863, when Abraham Lincoln ordered Thanksgiving to be celebrated on the last Thursday in November, that that date became generally accepted, Roosevelt explained. To make sure that reporters got his point, he added that there was nothing sacred about the date...

Just as he had done with his controversial "Court Packing" plan of 1937, Roosevelt had badly misjudged public opinion. Outraged protests began in Plymouth, Massachussetts, the place of the "first Thanksgiving" in 1621, but quickly spread to other circles, including, most notably, the competitive and highly lucrative world of collegiate sports.

PRESIDENT SHOCKS FOOTBALL COACHES: Many Games are Upset by Thanksgiving Plan, read a banner headline in the New York Times. And even in the staunchly Democratic state of Arkansas, the football coach of Little Ouachita College threatened: 'We'll vote the Republican ticket if he interferes with our football.'"

Of course, some college coaches and athletic directors were more diplomatic when it came to questioning the president. In a letter to the president's secretary, Philip Badger, Chairman of the University Board of Athletic Control at New York University wrote:

My dear Mr. Secretary:

I am wondering if you are at liberty at this time to supply me with any information over and above what has appeared in the public press to date regarding the plan of the President to proclaim November 23 as Thanksgiving Day this year instead of November 30.

Over a period of years it has been customary for my institution to play its annual football game with Fordham University at the Yankee Stadium here at New York University on Thanksgiving Day...As you probably know, it has become necessary to frame football schedules three to five years in advance, and for both 1939 and 1940 we had arranged to play our annual football game with Fordham on Thanksgiving Day, with the belief that such day would fall upon the fourth Thursday in November.

Please understand that all of us interested in the administration of intercollegiate athletics realize that there are considerations and problems before the country for solution which are far more important than the schedule problems of intercollegiate athletics. However, some of us are confronted with the problem of readjusting the date of any football contest affected by the President's proposal.

Outside of the world of collegiate sports, public opinion also ran heavily against Roosevelt's Thanksgiving Day plan, as evidenced by a national Gallup poll which found that 62% of Americans surveyed disapproved of the date change. And, as public opposition grew, some state governors reportedly "took matters into their own hands and defied the Presidential Proclamation."

According to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum:

Some governors declared November 30th as Thanksgiving. And so, depending upon where one lived, Thanksgiving was celebrated on the 23rd and the 30th. This was worse than changing the date in the first place because families that lived in states such as New York did not have the same day off as family members in states such as Connecticut! [And so] family and friends were unable to celebrate the holiday together.

By 1941, most retailers also disapproved of Roosevelt's plan, and even the federal government conceded that the date change had not resulted in any boost in sales. And so, on December 26, 1941, President Roosevelt signed Joint Resolution 41 making Thanksgiving a national holiday and mandating that it be observed on the fourth Thursday in November of each year.

FAST FACT: According to the Library of Congress, when "Abraham Lincoln was president in 1863, he proclaimed the last Thursday of November to be our national Thanksgiving Day. In 1865, Thanksgiving was celebrated the first Thursday of November, because of a proclamation by President Andrew Johnson, and, in 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant chose the third Thursday for Thanksgiving Day. In all other years, until 1939, Thanksgiving was celebrated as Lincoln had designated, the last Thursday in November."

Monday, November 7, 2011

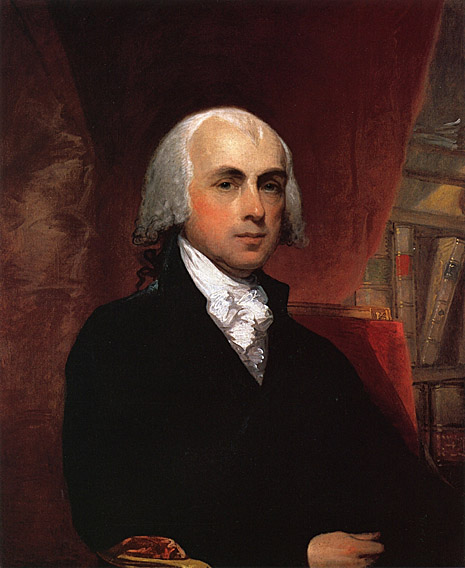

James Monroe, Mississippi Steamboatin' and "Food Piled High on a Long Linen Cloth"

So did you know that James Monroe was the first president to ride and possibly dine on a steamboat? By the 1820s, steamboats were in use on most of the major rivers, canals, and waterways in the United States.

So did you know that James Monroe was the first president to ride and possibly dine on a steamboat? By the 1820s, steamboats were in use on most of the major rivers, canals, and waterways in the United States. Historians say that the steamboat completely revolutionized shipping. For the first time in history, people "didn't have to rely on unpredictable currents and winds and could travel to any port at any time." Plantation owners in the southern states of Mississippi, Missouri, and Louisiana, for example, could cheaply and easily ship cargoes of sugar, cotton, and other goods upriver on the Mississippi rather than send it around the tip of Florida and up the Eastern seaboard as they had previously done.

Steamboats also provided a luxurious way for wealthy passengers to travel. In Mississippi Steamboatin’, Herbert Quick described the palatial setting and abundance of food served on later steamboats:

The palatial setting of later steamboats attracted pleasure-seekers and wealthy travelers...More comfortable than their 'settin' rooms,' more ornate than their prim and uncomfortable parlors...they saw the steamboat's cabin as a bewilderingly beautiful palace. The...glistening cut-glass chandeliers; the soft oil paintings on every stateroom door; the thick carpets that transformed walking into a royal march; the steaming foods piled high on the long linen cloth in the dining room, with attentive waiters standing at the traveler's elbow, waiting with more food, and gaily colored desserts in the offing - neither homes nor hotels...were ever like this.

Between 1814 (three years before Monroe took office) and 1834, steamboat arrivals in New Orleans increased from 20 to 1,200 each year. For the next half century, steamboats were the main transporter of American goods, and tiny river towns grew into thriving cities “when steamboats began to make regular stops at their docks.”

FAST FACT: If you've ever watched steam rise from a cup of hot chocolate or coffee, you might think that a steamboat is propelled by steam. That makes sense, but that isn't exactly how a steamboat works. In a steamboat's engine, wood or other fuel is burned to heat water in a boiler, and the steam that rises from the water is forced through small spaces (piston cylinders) to increase the speed at which it escapes, similar to the release of a valve on a pressure-cooker. The concentrated steam then hits and moves a paddlewheel which, in turn, propels the steamboat through water!

Credit: James Monroe, oil on canvas by Gilbert Stuart (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

James Madison, the Potomac Oyster Wars, and the Constitutional Convention

So you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly goes:

So you probably know that James Madison was one of the drafters of the Constitution and later helped spearhead the drive for the Bill of Rights, but what you might not know is that he also played a major role in negotiating an end to the Potomac Oysters Wars which indirectly helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention. This is how the story briefly goes: In the seventeenth century, watermen in Maryland and Virginia battled over ownership rights to the Potomac River. Maryland traced its rights to a 1632 charter from King Charles I which included the river. At the same time, Virginia laid its claims to the river to an earlier charter from King James I and a 1688 patent from King James II, both of which also included the river.

In 1776, after more than a century of conflict, Virginia ceded ownership of the river but reserved the right to “the free navigation and use of the rivers Potowmack and Pocomoke." Maryland rejected this reservation and quickly passed a resolution asserting total control over the Potomac. After the Revolution, battles over the river intensified between watermen from both states.

To resolve this problem, leaders from Maryland and Virginia appointed two groups of commissioners which, at the invitation of George Washington, met at Mount Vernon in May of 1785. James Madison led the Virginia contingent and Samuel Chase led the Maryland delegation. Their discussions led to the Compact of 1785, which allowed oystermen from both states free use the river.

Peace prevailed until the supply of oysters began to dwindle, at which point Maryland re-imposed harvesting restrictions. Virginia retaliated by closing the mouth of the Chesapeake and watermen from both states engaged in bloody gun battles which lasted, with periodic breaks, for more than a century.

Today, these battles are known as the Potomac Oyster Wars. They are important in their own right, but they have a larger historical significance because they revealed one of the main weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, which was that the federal government didn't have the power to control commerce among the states, a setup that was creating constant chaos and conflict.

With this problem in mind, Madison and the others who convened at Mt. Vernon in May of 1785 agreed to meet the following year at Annapolis to discuss the need for a stronger federal government. Not many delegates showed up and so they agreed to convene the following May in Philadelphia, which is, of course, where the Constitution was drafted.

And so NOW you know how James Madison and a little bivalve from the Potomac helped pave the way to the Constitutional Convention!

FACT: Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government didn't have the power to raise its own army, regulate commerce between the states, or coin money for the country. To pass a law, Congress needed the approval of nine out of the 13 states, and in order to amend the Articles it needed the approval of all 13 states, which made it nearly impossible to get anything done! The Articles also didn't provide for an Executive or Judicial branch so there was no separation of powers.